Military History

The Fortifications of Gibraltar

Al-Andalus

Despite Gibraltar having been the pivotal entry point for the Umayyad troops under Ṭāriq ibn Ziyād's command in 711 in their conquest of Iberia, no permanent urban settlement seems to have been built on the Rock until the 12th century. It was not until the Berber Almohads arrived on the scene that the first town was built in Gibraltar with Abd al-Mu'min having been credited with its construcion in 1160 and renaming Gibraltar Madīnat al-Fath (City of Victory). This first city included palaces, a mosque, fortress, port, residences, water reservoir and distribuition systems. Along the walls were towers and parapets where archers could be positioned. In 1309 Castile besieged and captured Gibraltar after little more than two months, in what would later become known as the First Siege of Gibraltar. We know that all earlier documentary evidence about Gibraltar changing hands do not mention any drawn-out attack or persistent resistance, which tells us that the Rock's defences were rather low-key before then, at least in comparison. Following this siege, Gibraltar became a Christian outpost in an otherwise Islamic hinterland.

Photo: Part of the Islamic city walls with a tower en bec, topped with merlons. (Wikimedia Commons/Prioryman)

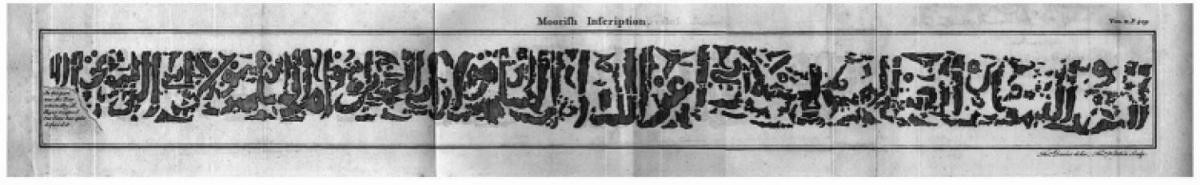

The Second Siege came as soon as 1316 but Castile held out. Acknowledging the the Rock's precarious survival, Ferdinand IV of Castile invested heavily in the city's defences, extending and reinforcing the walls and towers, and building a dry dock (atarazana). Nevertheless, the Marinīds were successful in the Third Siege of Gibraltar of 1333 with Sultan Abū l-Ḥasan ibn ʿUtmān's son Abū Malik capturing the city and establishing himself here. It was during this period that the defences of Gibraltar were seriously enlarged, first by the Marinīds who, between 1340 and 1350 carried out major constructions such as completing the seawall southwards to the area of Rosia Bay ("strong walls as a halo surrounds the crescent moon"), as well as major restructuring of the castle's main tower, which has survived to this day. The Nasrids who came later added to the construction frenzy and it was therefore during the 14th century that the walls we know today started to take shape. The scale of this construction is perhaps best illustrated by an inscription which once existed above one of the city gates.

Photo: The 'Tower of Homage' is the largest surviving remnant of the Islamic defences. The impact craters on its eastern wall probably date to the Third Siege of 1333, when Alfonso XI of Castille established three siege engines above the castle. (Wikimedia Commons/Prioryman)

Image: Muhammed V Arabic inscription from Thomas James' The History of the Herculean Straits (1771).

Spanish times

The Reconquista of Gibraltar took place on 20 August 1462, the feast day of St. Bernard who the Christians named patron saint of Gibraltar. The Eighth Siege brought an end to an Islamic Gibraltar, just over 751 years after Ṭāriq arrived at its shores.

The arrival of the Spanish in 1462 coincided with the period when gunpowder was starting to appear in large quantities, meaning that the defences had to be altered. High thin walls and round towers suitable for archers were replaced by low thick walls and square towers which could withstand cannonballs. The towers were also widened so that batteries of defensive artillery pieces could be mounted there behind embrasures (gaps in the parapet wall to fire through). As these towers stuck out from the ‘curtain’ walls in between, it meant that cannon mounted on the sides could fire across at attackers who got close enough to the base of the wall that the main line of guns could not fire down on them (this is called enfilading, or flanking fire). The largest of these towers were called bastions and were like mini forts with their own ammunition stores and troop shelters.

Image: Plan of Gibraltar by Luis Bravo de Acuña (1627).

Another addition during this period followed an attack in 1540 by pirates who landed at Europa Point and found the entire southern flank of the city unprotected. To rectify this, a wall was built from South Bastion towards the Upper Rock. This was strengthened in 1552, when Emperor Charles V sent Italian engineer Giovani Battista to improve the defences. The upper section was completed during the reign of Philip II, who succeeded Charles in 1558. It was during this period that bastions were added to the wall, though never fully completed.

Image: Detailed sketch of Gibraltar's Northern Defences by Anton van den Wyngaerde (1567).

British Gibraltar

Following the British capture of the Rock in 1704, they occupied and re-named the existing defensive positions and added more armament. There were two Spanish sieges, one the same year and one in 1727, causing a lot of damage, mostly to the batteries of the Northern Defences. These were repaired and added to using roughly-chiselled, unevenly sized white limestone blocks and grey mortar which typify British construction of this period. Good examples are the upper sections of North Bastion and Grand Battery. As Grand Battery protected the only land bridge into the city, it was supported by gun batteries on both sides which could provide flanking fire. In front there was a defensive ditch and beyond this a raised earthwork called a glacis. The glacis protected the front of the battery wall from artillery fire and also provided an exposed killing ground for any attackers on foot.

As the century progressed, so did the standard of the stone-working. Instead of the uneven, small pieces used before, in later constructions the stone was shaped into larger, rectangular blocks of the same height, which were laid in courses, like the rows of bricks in a modern wall. These large blocks were much more resistant to cannon-fire. A good example is the base of King’s Bastion.

William Green

Previous Spanish attacks had mainly been from the isthmus, so emphasis was always placed on the Northern Defences, but William Green, the new Chief Engineer for Gibraltar, realised that in future, sea assaults were far more likely. In 1770 he submitted very detailed proposals for the enhancement of the defences. The Line Wall would be strengthened against amphibious assault, with Howitzers and mortars placed there to destroy attacking ships. An extra gun platform called a cavalier was to be built on top of Montagu Bastion and Orange Battery up-graded to a half, or Demi-Bastion. A new, major 24 gun bastion was to be built halfway down the sea wall (this would later be called King’s Bastion) and Charles V Wall was to be strengthened and armed to protect the southern flank. Additionally, thick-roofed protective ammunition stores and barracks, called Casemates, were to be built to protect the troops in a number of locations. The proposals were adopted and work began straight away. Not everything was completed before the start of the Great Siege in 1779 and some works continued to be carried out even under enemy fire, but Green’s proposals proved crucial to the successful defence of the Rock.

King’s Bastion was General Eliott’s headquarters throughout the siege and the main gun platform engaging the floating batteries during the grand attack, hence it received a lot of fire. Casualty reports compiled after the attack showed that a large number of soldiers were incapacitated by flying fragments of limestone broken off from the sides of the gun embrasures, after they were struck by enemy cannonballs and musket balls. The limestone here was replaced by sandstone, which would turn to powder when hit, significantly reducing injuries. This sandstone is pink in colour and is obvious on the side batteries of King’s Bastion and many other batteries as well.

William Green remained active after the siege ended in 1783, later recommending the construction of counterguards on land reclaimed from the sea outside North, Montagu and Orange Bastions. These were thick walls forming an extra line of defence. At ground level there were casemates from where soldiers could fire their muskets through ‘loopholes’ at attacking troops. On the roof were embrasures for extra cannon. These were lower than those on the bastions, giving a double tier of cannon fire. The three counterguards, West Place of Arms, Montagu and Chatham, were built 1796-1804.

Sir John Jones

With the advent of faster, steam-propelled vessels carrying more powerful guns, the next important changes came following the visit of major-general Sir John Thomas Jones of the Royal Engineers in 1841. He proposed reinforcing the Line Wall with new, thicker walls, on which heavier cannon could be placed. To this end, casemated barracks and ammunition stores, topped with embrasures were built in front if the original Moorish line wall to form Wellington and Prince Albert’s Fronts. Wellington Front had a Left and Right Bastion, and Prince Albert’s Front a single, wide bastion called Zoca Flank Battery (zoca derived from the Moorish market, or ‘souk’ which was previously sited there). New curtain walls linked these bastions from South Bastion to King’s Bastion and from there to Orange and Montagu Bastions, which were also up-graded at the same time. In between the gun embrasures on top, raised steps called banquettes were built. Infantry soldiers could stand on these to fire their muskets down onto the enemy, then climb down to re-load in safety.

The limestone blocks for these were quarried locally and also shipped over from Portland in England. The development of steam-powered saws to cut the stone meant that these blocks have a much smoother finish and sharper edges than the hammer & chisel finished blocks on earlier walls and bastions.

Colonel William Jervois

In the 1860s, the appearance of fast, armoured vessels carrying much larger guns than previously, meant that Gibraltar’s defences became wholly inadequate. Following a report by Colonel William Jervois in 1868, the new large rifled muzzle loading gun (RML) was adopted for coastal defence. Some of these guns would be mounted in the South, or in retired positions higher up on the Rock, but others would be mounted on the existing bastions of the city walls, which had to be adapted to take them. Many small cannon gave way to a few large ones and low parapets with embrasures were replaced with large, stone clad side walls called merlons, which housed ammunition magazines. The area directly in front of the gun between the merlons was protected by the laminated teak and iron Gibraltar Shield which had a small gun port in it. In other areas, some of the RML positions were open-topped, but along the city walls all but South Bastion had overhead cover as well. The RMLs mounted along the city walls were as follows:

- South Bastion; 3x 10-inch guns;

- Wellington Front Right Bastion; 1x 12.5-inch;

- King’s Bastion; 4x 10 inch, plus 1x 12.5-inch;

- Zoca Flank Battery; 1x 12.5-inch;

- Orange Bastion; 2x 10-inch;

- Montagu Bastion; 3x 10-inch.

The dominance of the RML was short lived and in fewer than 20 years the Gibraltar RMLs became obsolete, without ever firing a shot in anger.

The Advent of the20th Century

This period saw two technological advances which would turn the defensive city walls into an historic relic. The first was the move to Quick-Firing (QF) Breech Loading (BL) guns. The largest of these had over four times the range of RMLs, so did not need to be close to the sea. Instead, they were mounted high up on the Rock, on protected rotating turrets, which gave them a much greater field of fire. They could destroy any large vessel approaching. The smaller guns were now mounted on the newly constructed moles, far in front of the walls, from where they could give short-range protection against small, fast craft trying to enter the harbour.

The second advance was the emergence of the aircraft as a weapon of war. An aircraft could fly straight over the walls and drop its bombs anywhere it wanted. The guns on the walls were too slow and could not be elevated high enough to engage these targets.

During the First World War, with no direct threat of invasion, many of these former batteries remained un-manned, or were used for storage.

Second World War

By the mid-1930s it was clear that war was looming and that Gibraltar would play an important role, therefore the defences started to be brought up-to-date. The bastions, although no longer suitable for coastal defence, did provide ideal platforms for anti-aircraft batteries, so they got a new lease of life. They were equipped with heavy 3.7 inch and light Bofors 40mm anti- aircraft guns, searchlights and troop shelters. These batteries saw action during the Italian and Vichy French air-raids of 1940-42.

World War II (WWII) construction is characterised by the use of concrete with iron reinforcing bars inside and corrugated iron sheets. Unfortunately, the concrete was mixed with seawater. Over time the salt causes a chemical reaction and the concrete starts to ‘spall’, or break up. The result is that the earlier British, Spanish and even Moorish constructions beneath are still in excellent condition, but the WWII additions are in a very poor state and many have been removed altogether.

18-20 Bomb House Lane

PO Box 939,

Gibraltar