Richard Ford’s visit to Gibraltar, 1845

Richard Ford’s visit to Gibraltar, 1845

We continue with Ford’s accounts of his visit to Gibraltar as he recounts its history:

“The fierce Berbers who accompanied Tarik had for ages before looked from the heights of the Rif on Spain, the land of their Carthaginian forefathers: many were their efforts to reconquer it even during the Roman rule, from the age of Antoninus (Jul. 13) to that of Severus (Ӕlian Sp. 64). These invasions were renewed under the Goths, especially in the 7th century (see Isidore Pac. i. 3). Their attempts failed so long as the Spaniard were strong, but succeeded when the Gothics house was divided against itself.

Gibraltar was first taken from the Moors, in 1309, by Guzman el Bueno; but they regained it in 1333, the Spanish governor, Vasco Perez de Meyra, having appropriated the money destined for its defence in buying estates for himself at Xerez. (Chro. Alonz. xi. 117). It was finally recovered in 1462 by another of the Guzmans, and incorporated with the Spanish crown in 1501. The arms are “gules a castle or and a key,” it being the key of the Straits. Gibraltar was much strengthened by Charles V. in 1552, who employed Jn. Ba. Calvi in raising defences against Barbarossa.

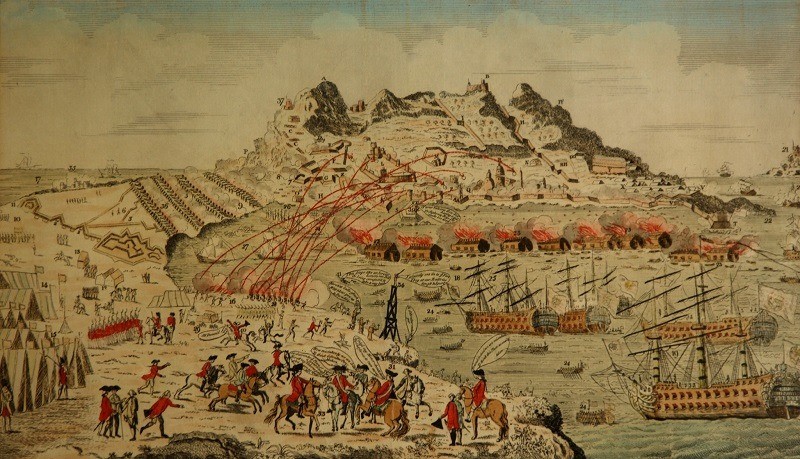

It was captured during the War of the Succession by Sir George Rooke, July 24, 1704, who attacked it suddenly, and found it garrisoned by only 150 men, who immediately had recourse to relics and saints. It was taken by us in the name of the Archduke Charles; this was the first stone which fell from the vast but ruinous edifice of the Spanish monarchy, and George I. Would have given it up at the peace of Utrecht, so little did he estimate its work, and the nation thought it “a barren rock, an insignificant cant fort, and a useless charge:” what its real value is as regards Spain, will be understood by supposing Portland Island to be in the hand of the French. It is a bridle in the mouth of Spain and Barbary. It speaks a language of power, which alone is understood and obeyed by those cognate nations. The Spaniards never knew the value of this barren rock until its loss, which now so wounds their national pride. Yet Gibraltar in the hands of England is a safeguard that Spain never can become a French province, or the Mediterranean a French lake. Hence the Bourbons north of the Pyrenees have urged their poor kinsmen tools to make gigantic efforts to pluck out this thorn in their path. The Siege by France and Spain lasted four years. Then the very ingenious Mons. d’Arcon’s invincible floating batteries, that could neither be burnt, sunk, nor taken, were burnt, sunk, and taken by plain Englishmen, who stood their guns, on the 13th of Sept. 1783. Thereupon Charles X., then Count d’Artois, who had posted from Paris to have glory thrust upon him, posted back again, after the precedent of his ancestors, those kings of France with 20,000 men, who march up hills, and then march back again. He concealed his disgrace under a scurvy jest: “La batterie la plus effective fut ma batterie de cuisine.” Old Eliott stood during the glorious day on the “King’s Bastion,”Gen¹ Boyd, by whom it was erected in 1773. Boyd, in laying the first stone, prayed “to live to see it resist the united fleets of France and Spain.” He dies to carry out his prophecy; and in it he lies buried, a fitting tomb: Gloria autem minimé consepulta. Gibraltar is now a bright pearl in the Ocean Queen’s crown. It is, as Burke said, “a post of power, a post of superiority, of connexion, of commerce; one which makes us invaluable to our friends and dreadful to our enemies.” Its importance, as a dépôt for coal, is increased since steam navigation. Subsequently to the storming of Acre, new batteries have been erected to meet this new mode of warfare. Sir John Jones was sent out in 1840, and under his direction tremendous bastions have been made at Europa point, Ragged Staff, and near the Alameda: while heavier guns have been mounted on the mole and elsewhere. Nor need it be feared that the bastions and example of Boyd will ever want an imitator in sæcula sæculorum.”

Image: A view of the Rock and Town of Gibraltar attacked by Sea and Land by the combined forces of France and Spain under the Command of the Duc de Crillon and in the presence of the Comte d'Artois in September 1782.

Published: July 05, 2020

Other similar VM - Historical Notes from our Archive

VM - Historical Notes from our Archive

Historical notes from our archive Café universal

Published: March 25, 2020

VM - Historical Notes from our Archive

Historical notes from our archive Guillem & Roscelli pharmacy, Waterport street

Published: March 26, 2020

VM - Historical Notes from our Archive

Historical notes from our archiveCalpe Sextet & Mrs. Amar

Published: March 27, 2020

VM - Historical Notes from our Archive

Historical notes from our archive Hermanos Cavilla

Published: March 28, 2020

VM - Historical Notes from our Archive

historical notes from our archive King's Arms Hotel and Victoria hotel

Published: March 29, 2020

18-20 Bomb House Lane

PO Box 939,

Gibraltar