palaeontology rosia bay and the beginnings of life and earth sciences

Palaeontology Rosia Bay and the beginnings of life and earth sciences

The first studies using the scientific method in relation to the Earth’s history and human origins (geology, palaeontology, archaeology, etc.), date back to the 18th Century. Gibraltar has played a leading role since those early days, which continues to this day.

Science, at the time, was still largely dominated by theories that were directly based on biblical texts to explain our past. A good example of this were the calculations made by the Church of Ireland’s Archbishop of Armagh, James Ussher, to calculate the age of the Earth in 1625. By looking into the genealogy of Genesis, Ussher dated the origin of the Earth and all its component parts to Sunday 23rd October 4004 BCE. Many believed this to be true even up until the 18th Century.

The first known notes on the geology and palaeontology of Gibraltar are from the 18th Century, with Rosia Bay having been at the very centre of this early research, playing a leading role in important scientific publications. As early as 1769, the chaplain at Gibraltar Reverend John White, having seen the fossil-rich breccias of Rosia Bay and after collecting zoological specimens to send to his brother, the naturalist Gilbert White, asked himself about the possibility of finding human remains. Upon his return to England, he wrote what is considered to be the first detailed zoological account of Gibraltar, ‘Fauna Calpensis’. However, his work was never published and has unfortunately been lost together with his collections and most of his notes.

Breccias are conglomerate rocks composed of fragments of stones or minerals cemented by a fine-grained matrix. They may contain bones or shells which after having been buried by a fine layer of sediment become consolidated and compacted over time. These deposits are very common in Gibraltar, with the cementing agent being the calcium carbonate that leaches out of the limestone when rain percolates through this porous rock.

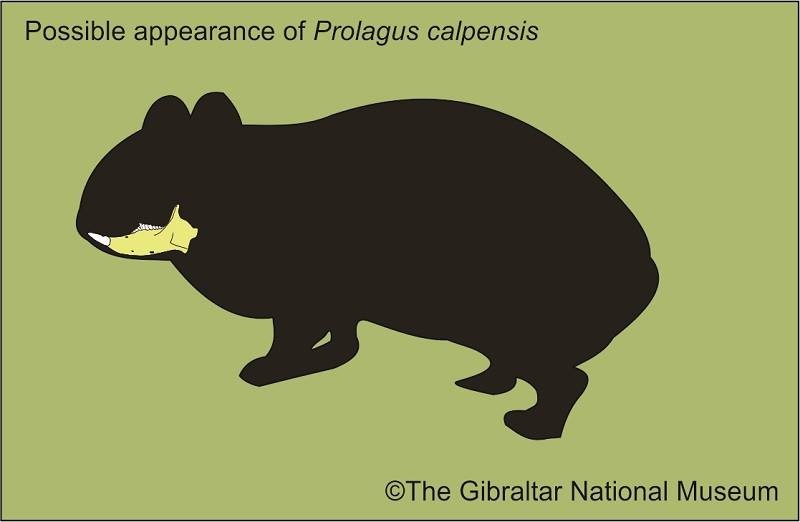

The first published references to Rosia Bay are in the 1770 correspondence between Boddington and Hunter which includes a general description of the geology of the Rosia breccias, mentioning the presence of fossils. Part of these were described by one of fathers of modern palaeontology and forerunner of comparative anatomy, George Cuvier, who in 1823 records the presence of skeletal remains from the suborder of ruminants and a species of lagomorph (rabbits, hares and pikas) previously unknown to science.

It was not until 1905 that Forsyth Major would describe this species of extinct lagomorph, by relating it to living pikas, as ‘Prolagus calpensis’ in honour of its first ever discovery having been at Rosia Bay (Calpe being the ancient name for the Rock of Gibraltar).

Published: April 06, 2020

Other similar VM - Paleontology

Virtual Museum VM - Paleontology

A metapodial fragment belonging to an Aurochs

Published: June 28, 2020

18-20 Bomb House Lane

PO Box 939,

Gibraltar